Democratizing autonomous driving research and development

Largely based on Dr. Holger Caesar's research talk at UP EEEI

Recent advances in computer vision and artificial intelligence paved the way for major leaps in machine perception and understanding–key elements of autonomous systems. As a result, autonomous vehicles (AVs), particularly self-driving cars, have risen in popularity in the past several years. Tesla is arguably the most well-known company in the AV space. Autonomous taxis–or robotaxis–are also gaining traction. Waymo (formerly the Google Self-Driving Car Project) and Motional (formerly nuTonomy) are two of the several companies competing in the AV industry.

The case for autonomous vehicles

Enhanced safety is one of the primary motivations for developing AV technology.

In autonomous vehicles, the degree of autonomy is classified into 6 levels. Level 0 pertains to the case where a human is 100% in control of the vehicle and no automation is employed. Meanwhile, the other end of the spectrum is Level 5–the fully autonomous case–where a human is merely a passenger in a driverless car. As of this writing, no system has achieved Level 5 yet.

Waymo was the first to achieve Level 4 autonomy, or high driving automation. At Level 4, a vehicle is autonomous only for certain specific conditions or geographical areas, e.g. driving in the freeway, or backing out of a garage. In contrast, Level 5 AVs are fully autonomous 100% of the time, and should be able to seamlessly cooperate with each other, enhancing passenger safety and reducing–if not totally eliminating–human-caused accidents.

Road to full autonomy

How do we progress from the current state-of-the-art, Level 4, to the next frontier–Level 5? This is one of the key problems being tackled by Dr. Holger Caesar, Assistant Professor at TU Delft and former Principal Research Scientist at Motional. In his talk at the Electrical and Electronics Engineering Institute in UP Diliman last May 9, 2024 (Figure 1), he highlighted the important correlation between the number of human interventions per mile driven and training data quantity, as shown in Figure 2. Interventions per mile driven is used by the California Department of Motor Vehicles as a proxy measure for AV safety, where lower number of interventions mean safer autonomous vehicles. This measure is considered the industry standard.

{

"tooltip": {

"trigger": "axis"

},

"xAxis": {

"type": "log",

"name": "Training dataset size (hours)",

"nameLocation": "middle",

"nameGap": 20,

"max": 2000

},

"yAxis": {

"name": "Interventions per 1,000 miles",

"nameLocation": "middle",

"nameGap": 40

},

"series": [

{

"data": [[3.5, 2190.7], [10, 1024.1], [100, 145.3], [1000, 93.9]],

"type": "line",

"label": {

"show": true

}

}

]

}

While larger AV datasets are desirable, the costs associated in acquiring them are not. Data acquisition costs increase with the amount of data collected and annotated. Manually annotating vast amounts of data is prohibitively expensive. As Dr. Caesar remarked, only billion-dollar companies could afford to annotate such large-scale datasets. What is the solution then?

Towards affordable large-scale autonomous driving datasets

Due to significant differences in traffic rules, infrastructure, and road user mix across countries, or even cities, a dataset is inherently tied to the place where it is acquired. Therefore, city-specific datasets are preferred since models trained on these will always outperform generic ones.

Aside from the technical aspects, there are human factors involved too. In the Philippines, for example, workers often face “digital sweatshop” conditions because the data annotation industry is still considered an informal sector and is unregulated.

Dr. Caesar highlighted the need for affordable dataset acquisition in order to democratize autonomous vehicle research. Without an affordable way to acquire data, countries lacking in resources will be left behind, and human annotators will continue to be exploited. The following sections discuss the three key ingredients of the affordable auto-labeling framework he proposed.

Ingredient 1: Unsupervised object discovery and self-supervised learning

Unsupervised and self-supervised learning are learning paradigms which take advantage of vast amounts of unlabeled data. While the two terms are oftentimes used interchangeably in the literature, there is a nuanced difference between them

Dao et al.

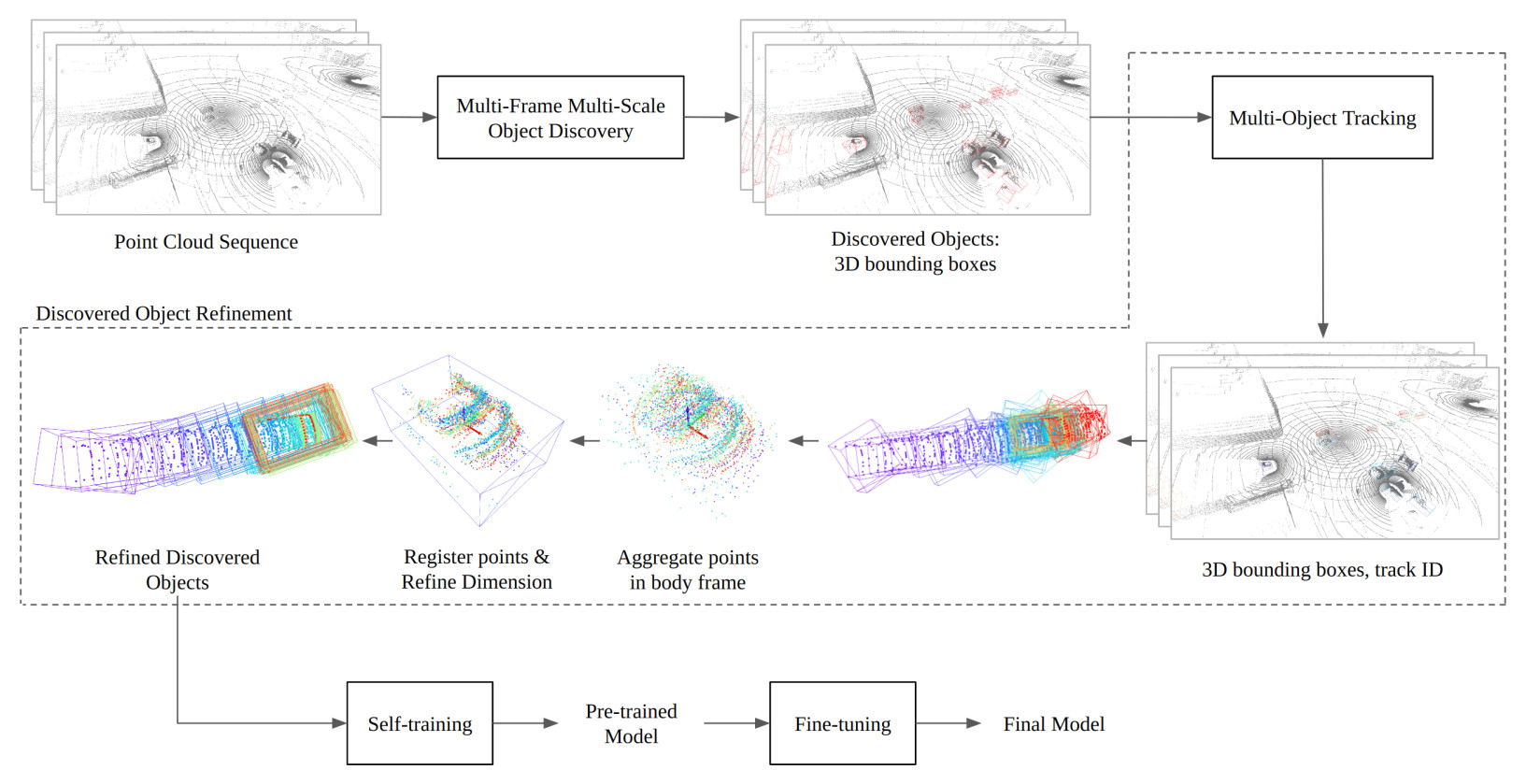

Figure 3 illustrates the overview of their method. Self-training is done as follows:

- The output of the unsupervised object discovery method serves as the initial labeled training data.

- An initial detection model is trained on this initial dataset.

- Once trained, the detection model is then used on the training set to detect objects. Only the high-confidence detections are selected, and these are treated as ground-truth. In the literature, these model-generated labels being used as ground-truth are called pseudo-labels.

- The pseudo-labels are then used to train a new detection model, and the cycle is repeated (steps 3 and 4) until a satisfactory level of performance is achieved.

Using their proposed method, the same performance can be achieved with 2-5x less manual annotation effort.

Ingredient 2: Active learning

In machine learning, training on more data is generally better. At some point however, the cost of annotating a data sample exceeds the benefits of being able to use that labeled sample for training. Model performance will start to saturate at some point, and using more data beyond that no longer makes sense. Furthermore, the resources available–money–limit the amount of data which can be acquired. Therefore, machine learning practitioners should be clever and efficient in choosing training samples. In other words, the goal is to minimize the training data required to meet the desired model performance.

Large datasets are bound to have redundancies. Active learning is a learning paradigm which focuses on the selection of the most informative representative samples from a large pool of (possibly unlabeled) data. Jacob Gildenblat’s article provides a more comprehensive overview of active learning in the context of deep learning.

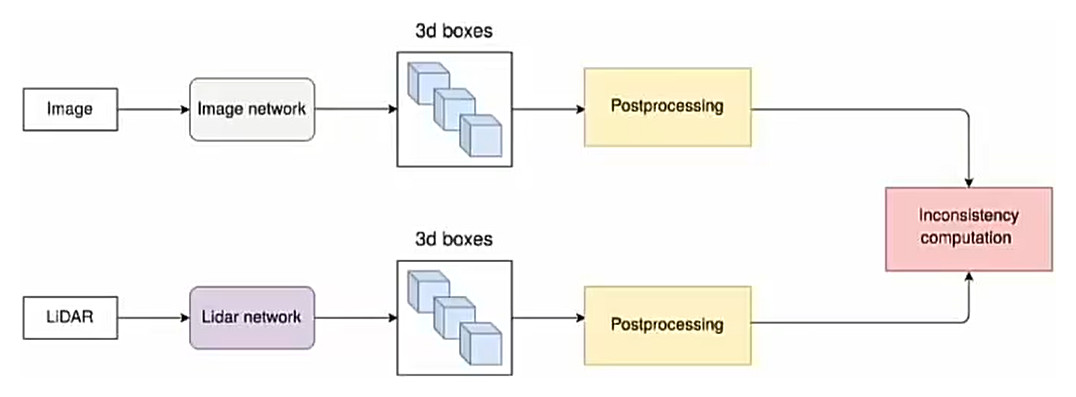

The patent of Tan et al.

Ingredient 3: Foundation and Language Models

Training a large model from scratch requires massive datasets and tremendous compute power. However, not everyone has the resources to do this. To lower the data requirement and shorten the training time, an initial condition close to a local optima is crucial. When two tasks are similar enough, existing trained weights can be reused instead of resorting to random initialization. This is the key idea behind transfer learning and finetuning.

The introduction of the Transformer

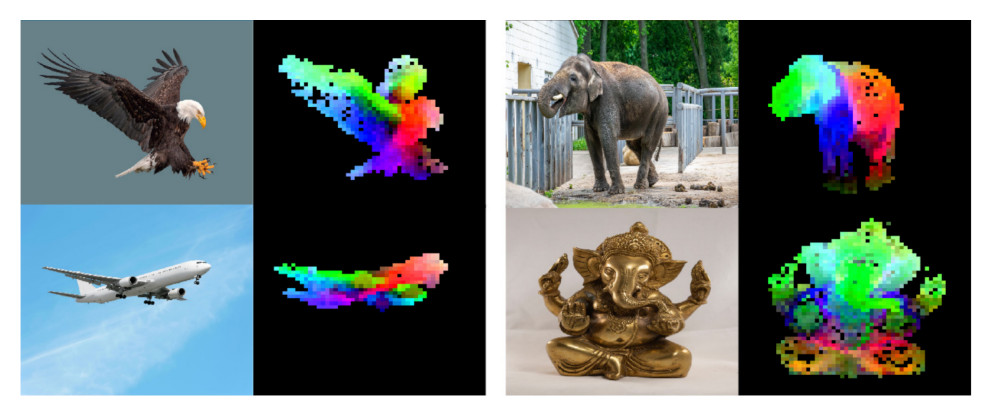

Desirable properties–such as understanding of object parts–typically emerge in self-supervised vision models like DINO v2

Conclusion

Safety is one of the driving motivations behind autonomous vehicle research. By eliminating the possibility of human error, autonomous vehicles are touted as safer alternatives. However, we are still far from achieving fully autonomous vehicles which could operate reliably in diverse and unpredictable environments. One of the major roadblocks is dataset acquisition. Autonomous vehicles would require vast amounts of annotated data in order to reach a full degree of autonomy.

Large-scale manually annotated data is not economically viable, even for big well-funded companies. Thus, we have to be clever about data acquisition while simultaneously developing label-efficient training methods. Dr. Caesar presented a framework for democratizing autonomous vehicle research by making dataset annotation more affordable. By using unsupervised and self-supervised methods, active learning, and foundation models, auto-labeling can be made cheap and effective. Future work should tackle how to use these three ingredients in synergy.